New York’s First Narcan Vending Machine Is Working

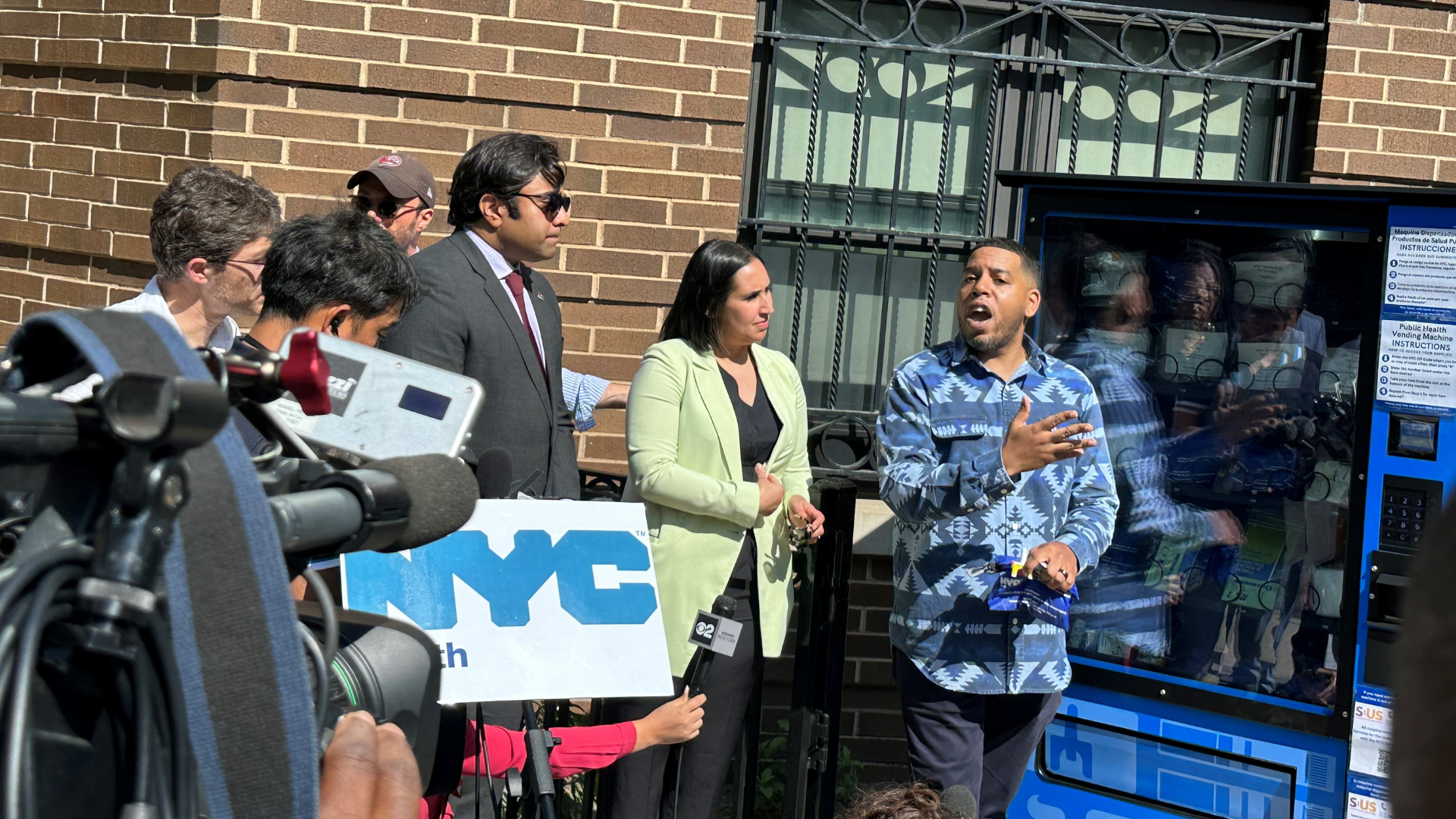

Photo caption: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Commissioner Ashwin Vasan, MD, PhD and S:US Chief Strategy Officer Rebecca Linn-Walton, PhD, LCSW watches as S:US Opioid Overdose Program Director Elan Quashie demonstrates how to access the public health vending machine.

July 5, 2023

Curbed

By Wilfred Chan

One afternoon in the middle of June, Elan Quashie had just finished restocking the vending machine outside of the Brownsville nonprofit where he works when a co-worker told him a man was slumped over next to it. Quashie suspected that the man was overdosing on fentanyl and immediately jumped into “training mode”; as the overdose program director at Services for the UnderServed, he has spent nearly a decade teaching people how to use naloxone, also known as Narcan, to reverse overdoses. But he had never done it in real life.

After calling for an ambulance and rubbing his knuckles on the man’s sternum to wake him (this didn’t work), Quashie punched some buttons on the vending machine to get a pack of Narcan nasal spray. He pushed one dose into the man’s nose, and then, when that didn’t seem to revive him, another. The unconscious man finally stirred awake. He was confused — the last thing he remembered was looking for a place to sit down. New York’s first naloxone vending machine had only been installed on the sidewalk days earlier, and it had probably saved his life.

The encounter was over in just a few minutes, but “it just gave me goose bumps,” Quashie says. “Even if I wasn’t there, anyone could have used the machine and done that in real time.” It’s that easy access that motivated the city’s health department to install one, and soon at least three more across the city. The nondescript blue appliance, which looks like a regular vending machine from afar, isn’t only stocked with Narcan; it offers fentanyl and xylazine test strips, clean pipes, and basic health supplies like maxi pads, toothbrushes, condoms, and wound-care kits for free. But it’s the Narcan and other drug-related items that have drawn most of the attention and made it a divisive symbol of the city’s attempts at harm reduction — an approach that offers compassion and practical services to drug users with the goal of keeping them alive rather than pushing sobriety or punishing them. The vending machine, not surprisingly, is already the subject of histrionic tabloid coverage (it was recently called a “white flag of surrender to addiction” by the New York Post board). The reality that I found is that it’s a new experiment for everyone — and a source of cautious hope.

Nearly 2,700 New York City residents died of drug overdoses in 2021, the highest number since the city began tracking the numbers two decades ago, and 2022’s total is expected to be even higher. Brownsville had one of the highest rates of death from overdoses in 2021. City health officials say it’s a crisis that could spiral out of control without an all-out intervention. “Every three hours, we’re losing a New Yorker,” said the city’s health commissioner, Dr. Ashwin Vasan, at the machine’s launch event. “To reverse those trends, it’s going to require more tools like this.”

The logic behind the vending machine is straightforward: If you meet people where they are, you can lower their barriers to getting life-saving care. Harm reduction has long been an accepted principle of public-health policy in countries like Canada and Australia, and in many parts of Europe, but has only recently started gaining traction in the United States. In New York City, one of the most active testing grounds, early efforts in East Harlem and Washington Heights seem to be working. The two safe-consumption sites that the city opened in these neighborhoods in 2021, the first in the country, allow people to use drugs while supervised by trained clinicians, without judgment or fear of arrest. Despite disdain and disapproval from right-wing commentators and local residents, the nonprofit that operates it says it’s already intervened in more than 850 overdoses since opening. By installing naloxone vending machines, the city hopes to make getting help even easier.

On a warm Wednesday afternoon, the vibe is downright tranquil on Broadway and Decatur Street, where the vending machine stands at the foot of the elevated J/Z subway tracks. Stationed next to the nonprofit’s entrance, it’s actually easy to miss. There’s not a ton of foot traffic, and most pedestrians don’t even glance at it. The workers at neighboring bodegas, stores, and restaurants are mystified when I mention it. In nearly half a day of loitering around the site, I encounter just a handful of nearby residents who have heard of the machine at all.

Naloxone vending machines have only been around for a few years in the United States. One of their biggest champions is Matthew Costello, a manager at Wayne State University’s Center for Behavioral Health and Justice, who works on substance-use and overdose-prevention programs at Michigan jails. “Data shows us that time and time again, individuals who are released from a correctional facility who have a history of using opioids are considerably more at risk for overdosing than any other population,” he says. Costello’s team had initially considered slipping Narcan into releasees’ property boxes, but rejected it. “We wanted an individual to be able to make that decision themselves,” he says. In 2019, he realized vending machines were “the perfect idea.”

Since 2021, Costello has helped place 35 machines and counting throughout Michigan, funded by public and private grants. They’re placed in jails as well as public sites, where they’re operated by local community groups. Just a few weeks ago, a Wayne State pharmacy student used a dose of Narcan he’d gotten from a vending machine to save a stranger’s life. But it’s difficult to track exactly how well the machines are working. “When you want to measure that, you start gathering identifiable data on people, and that’s counterintuitive for the population that we’re trying to impact,” Costello says. So his team has settled on a simpler benchmark of success: “Just flood the market as best we can with a tool that saves lives.”

New York follows the same principle of protecting users’ privacy. The vending machine only requires that people enter a New York City Zip Code on the keypad to get an item. After that, there’s no limit to the number of items they can take. Rebecca Linn-Walton, Services for the Underserved’s chief strategy officer, compares the vending machine — which costs roughly $11,000 — to a community fridge. “So often, people don’t come into care because they think they’ll be judged. And so if we can have a non-stigmatizing, bright, shiny blue, beautiful box on the street, people will feel comfortable getting the tools they need,” she says.

What about the unlimited supply — wouldn’t someone be tempted to take more than they actually need? Linn-Walton isn’t worried about that. “To my mind, if people are taking everything out of it, it’s because they need it. If somebody thinks they need 30 Narcan kits to use safely, good for them. Let them live. That’s all we want.” Quashie says that in the two weeks since the machine’s launch, people have taken an average of nine Narcan kits a day, and he generally restocked it about three to four times a week.

The vending machine’s most controversial item is a safer-smoking kit, which includes a clean crack pipe, a mouthpiece, and lip balm. Its purpose is to prevent infections and burns “so people don’t get horrific blisters on their face if they’re smoking,” Linn-Walton says. But critics have seized on it as yet more evidence of New York City’s lawlessness. After the first few kits were dispensed at the launch, a New York Post headline blared “NYC’s Drug-Themed Vending Machine Cleaned Out of Crack Pipes Overnight.” William Bratton, the former NYPD commissioner, said on a radio show last month, “Instead of trying to get people away from drugs, we have policies now where we have vending machines to encourage them to stay on drugs.”

That doesn’t seem to be happening. Veronica Lopez, a homeowner who lives down the block on Decatur, tells me she’s noticed “a lot of people taking pictures” of the machine but not much else happening around it. She’s never heard of the term harm reduction, but when I explain how the machine works, Lopez lights up. “I know a few people for whom this would be very helpful,” she says.

As I talk to someone in front of the machine, a cop pulls up and gets out of his squad car. I tense up, wondering if he’s going to question me. But he says he just wants to look at the machine. “I haven’t seen anyone use it yet,” he says. “This is the first time that I’ve actually approached it to see what it’s for.”

I ask if he’s heard of the term harm reduction, and he says he hasn’t. But when I tell him its general tenets, he nods. “It makes sense. There’s not only one way to solve the issue,” he says, before asking to be left unnamed in my story.

It turns out that the people with the strongest opinions about the vending machine are the ones who live directly above it, in Services for the Underserved’s supportive housing. Doug Czarnecky, a lanky older man, is dismissive. “It won’t help,” he says, explaining that he used drugs in his 30s and quit through “willpower.” Another resident, who doesn’t want to provide her name, says the machine’s location next to the building’s entrance makes the whole place “look bad.” “There are people here who aren’t just using drugs,” she says. “They’re addicts. Addicts!”

It’s nearing nightfall when I meet someone else who’s used the machine. He’s a middle-aged supportive-housing resident named Tory Wigfall, who had used the machine just once before, to get some alcohol wipes to clean his sneakers. He’s surprised when I tell him there’s no limit to how many items he can take. Punching in his Zip Code, he grabs a Narcan kit, a hygiene kit, xylazine test strips, and some Band-Aids — which he immediately wraps around a wound on his pinkie. “I was skeptical at first,” he says. “You don’t normally see things like this in any neighborhood. But it’s fortunate that we have something like this.”

As we chat in the machine’s glow, we’re approached by a woman who is crying, with disheveled hair, smeared makeup, and open wounds on her face. She tells us she was just fired from her job and needs some money for the train. As I hand her a few bills, Wigfall turns to the machine and gets a hygiene kit and some xylazine test strips for her. She looks stunned and gasps, “Thank you” between sobs. “Everything’s free,” Wigfall reassures her. “Get yourself some good rest tonight and start over tomorrow.”